Dedicated to the memory of:

Lieutenant

David Hugh Russell Tinker

HMS Glamorgan

RESURRECTION

And when the barge from Avalon comes back

I shall stand watching it, with you,

And your blonde hair shall ruffle in the breeze

And you shall say “I will forgive”

And time will vanish from that hallowed place.

Then will your smile return

Because your youth has come again

And we shall stand together as we watch

The last waves roll in, one by one.

Then night shall come, and we will camp

Around the shores, and watch our lives go by,

And I will cradle you within my arms

And feel your love flow back to me.

Then all the twinkling lights shall be snuffed out

And tombs shall stand erect against the sky

And dawn shall never come.

Then shall the rain come sweeping from the west

And glistening church towers shall ring their peals

And we shall raise ourselves from sleep

And sons shall find their mothers once again

And we shall walk towards the kirk, where

Christ is walking through the daffodils.

David Tinker, 20.4.73, aged 16

Swynnerton Training Area, the 1978 Battle Efficiency Patrol Competition.

2/Lt Graham Jardine, O/Cdt Alan Gibson, 2/Lt Bob Meneer (Acting Sgt), 2/Lt Matt Worden (Acting L/Cpl), 2/Lt Gus Pugh (Gunner).

O/Cdt Dave Pointet, O/Cdt Phil Morrel, Sub/Lt Dave Tinker, JUO Jim Taylor, 2/Lt Graham Martin (Acting Cpl).

Sunset on the 12th June 1982, at position 51° 50.5’S 053° 31.2’W

Extract from “One Hundred Days” by Admiral Sandy Woodward, used at his suggestion.

Glamorgan had been detached inshore as usual at about 1700 to go to her gun line south of Port Stanley by 2330 – this meant making twenty-six knots just to get there. As usual, the ship’s company went to Action Stations before entering the threat area, on this occasion at 2315, and remained at full alert throughout the night. The ship was operating very close inshore, with Yarmouth and Avenger in company, providing artillery support for the various actions being undertaken by the land forces that night. Her guns were being directed from the high ground by a naval ‘spotter’ until he was wounded, and then by a bombardier. She fired fairly continuously as the Commandos went forward to Two Sisters. The guided-missile destroyer and Yarmouth between them sent in over four hundred shells before the ships began their withdrawal at 0515. They were, in fact, a bit late in leaving because the Commandos were having a tough time on the mountain. The ship’s company of Glamorgan were stood down from Action Stations at 0530, conscious of a good night’s work.

When finally they did break away from the Stanley gun line, I thought at the time that Glamorgan just miscalculated the edge of the ‘envelope’ we had designated as being within range of the shore-based Exocet launcher on the road at the back of Port Harriet. But it is likely that the Argentinians had managed to move their mobile launchers a shade further east along the coast. Either way, at 0536 the Argies fired one. Avenger saw it ten miles out, sounding an alarm shortly after it had been sighted visually in Glamorgan. The helm was put hard over to turn away from the missile, quite possibly saving the ship by doing so. At one-mile range they fired Seacat and, with Glamorgan still heeling to her turn, the missile clipped the upper deck exactly where it joins the hull on the port side and blew up just short of the hangar.

It killed eight men instantly and wiped out the Wessex helicopter. Burning fuel poured through the hole in the deck and started a fire in the galley. Four cooks and a steward were killed in here and there were several other injuries. Smoke was sucked into the gas turbine room, but these engines were only temporarily put out of action by the blast effect of the Exocet explosion and by the water used for fire-fighting draining down through the splinter holes, causing flooding. Glamorgan was, rather remarkably, still well able to steam and, after sorting out the immediate problems, soon worked up to twenty knots to rejoin the Battle Group. I expect the British troops on the mountains watched her go with some sadness. Mike Barrow’s ship had been an exceptionally good friend to them that night and for many, many nights before.

Thirteen of Glamorgan’s gallant company died, nearly as many as 3 Para in their grim fight for Mount Longdon. And so, while they built a small memorial to Sergeant Mackay up on the frozen heights of Mount Longdon – just his rifle, a Para’s helmet and a small jam jar of daffodils on the spot where he fell – we once more buried our dead at sea. Among the Royal Navy coffins which slid into the endless silence of the Atlantic depths one hundred and sixty miles east of the Falkland Islands that evening, was that of twenty-five-year-old Lieutenant David Tinker, who was killed in the hangar. He was a sensitive, intelligent young officer, with a love of literature and poetry and for this he will be remembered, for his father published a truly poignant book of his letters and writings later that year.

Essentially, this widely read book is a hymn against war and all that it stands for and in subsequent years has been recognised as a kind of cry, from beyond the grave, of a young man who understood the wickedness of it all. Almost with each letter he grew more certain of the foolishness of the conflict. He felt that Margaret Thatcher had Churchillian delusions of ‘defying Hitler’, that John Nott did not understand what war was like, that I ‘seem to have no compunction about casualties at all’. He wrote of ‘the military fiasco’, the ‘political disgrace’, and wondered ‘if I am totally odd in that I utterly oppose all this killing that is going on over a flag’. He even mentioned the rate of fuel consumption perpetrated by his own ship Glamorgan as she made her escape from the waters around Pebble Island on 14 May … 33,000 gallons, six yards a gallon, was his assessment. That actually sounded a bit steep to me.

Nonetheless, his was a voice which ought not to be ignored. It presents a point of view far removed from mine, but it was still a valid point of view. A well-written one too. Indeed some of his assertions – for instance, that the British government had been planning to ‘leave the islands totally undefended and take away the islanders’ British citizenship’ – were a bit too close for comfort. And what, you might ask, was a chap like this doing on the flight deck of a 6000-ton British destroyer in the middle of a war? It’s a good question. The truth is that David Tinker was what is known as a VOLRET, a man who had applied to resign his commission in the Royal Navy (voluntary retirement). He had made his application some time before the Falklands problem arose. He was not a chap who was just trying to get out, at the prospect of having to go and fight. I think he was sincere in his belief that a career in Her Majesty’s armed forces was not for him and that having been married for a couple of years he wished to lead a more settled life ashore. There is nothing wrong with that.

Family and friends are encouraged to contribute.

We will add information to this memorial as we receive it.

If you have a photo, an anecdote, or simply to say you remember him, we will be very pleased to hear from you, so please contact the sama office at [email protected]

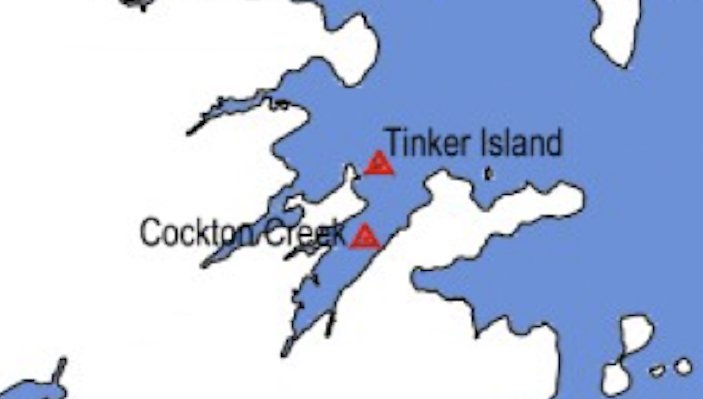

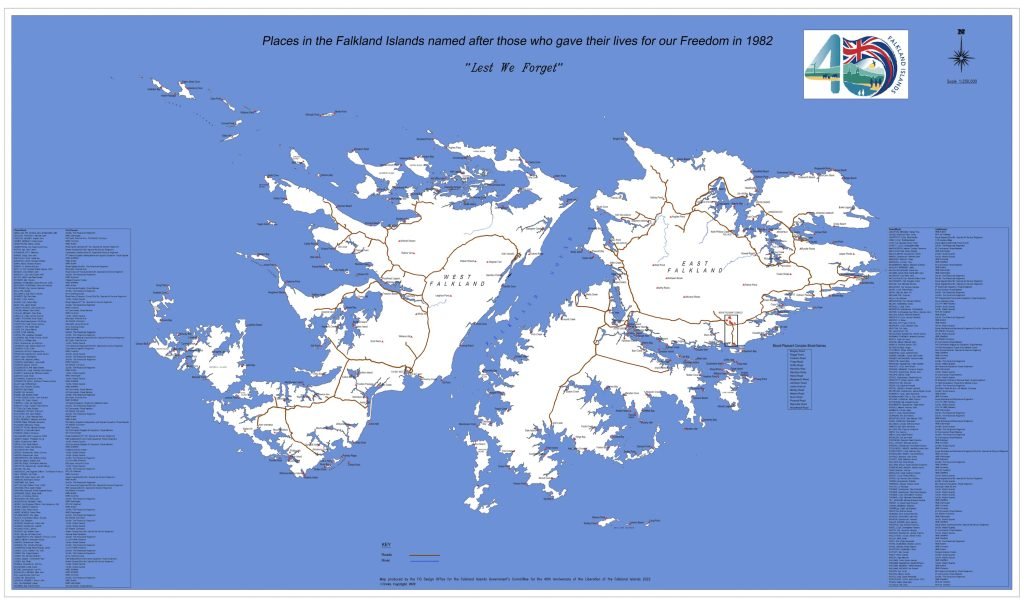

In 2022, as part of the 40th Anniversary commemorations, geographical features were identified and named after the fallen of 1982. TINKER ISLAND is a small vegetated island off Island Point, on the west side of the Bay of Harbours, East Falkland.

It is in position

52° 12′ 15.48″ S, 059° 23′ 58.25″ W