For Your Eyes Only - Part Two

Written by Paul McKay, HMS Brilliant 1982

Nelson’s Trafalgar ‘England expects ….’ is embedded in naval psyche. But another event in naval folklore inspired us to attempt a hairy escapade this night.

The Royal Navy launched an audacious attack on the Italian fleet in Taranto harbour with ship launched aircraft in 1940. It is celebrated every November in the Fleet Air Arm. Inspired by the men of Taranto, a ship launched helicopter attack in 1982 drew no such acclaim, but as at Taranto, the aircrew knew their lives were expendable and they were prepared not to return from the mission.

Image: Flying through Anti-Aircraft Fire at Taranto 1942

Image: Flying through Anti-Aircraft Fire at Taranto 1942

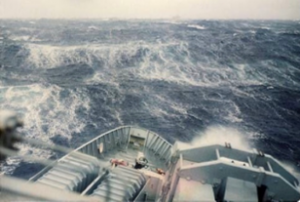

On 14 May 1982, the Type 22 Frigate HMS BRILLIANT was protecting the British Battle Group, the aircraft carriers HMS INVINCIBLE and HMS HERMES east of the Falkland Islands, to place the Argentine Air Force at extremity of its missile and bomb attack range. The weather all week had been seasonal wintery gales and getting worse, reducing the possibility of air sorties taking off from the Argentine mainland. HMS BRILLIANT used the opportunity to rendezvous with an auxiliary supply ship to take on stores by Replenish At Sea but the swell was so bad that ships could not get alongside each other and hold position safely; so, we replenished using the ship’s Lynx helicopters flying the heavy stores from ship to ship as underslung netted loads. A long and tiring flight but the ship’s crew were happy as we landed mail and news from loved ones back home.

We were scheduled to fly again that afternoon in an early warning role, to the west where Argentine attacks were expected to come from but the sea became so rough with the approaching storm that it wasn’t possible to move the helicopter from the hangar to the flight deck with water up to our shins. It looked as if I was going to get some needed rest from flying duties when I was called to a briefing in the Captain’s cabin. This was the first of several briefings over a few hours with each becoming tenser and a tadge confrontational.

Throughout the week, British frigates and destroyers had been dispatched under cover of darkness from defending the British Battle Group in the Southern Ocean to search for and destroy Argentine ships supplying troops, and for the insertion of Special Forces on East and West Falkland Islands. The mission HMS BRILLIANT was given this night, seemed at face value to be straight forward – to seek and destroy the Argentine Supply Transport Ship, ARA BAHIA BUEN SUCESO. Intelligence reported her in the vicinity of Fox Bay, West Falkland.

Image: Running ahead of a storm in typical South Atlantic weather

Image: Running ahead of a storm in typical South Atlantic weather

Captain Coward, HMS BRILLIANT described as one of the last pirate submariner captains, had the bit between his teeth. Being given the order from Admiral Woodward on the Flagship HMS HERMES he pushed his warfare team hard for a plan to take a ‘prize’ this night. The mission had to be carried out at night to be back on station with the Battle Group by sunrise. British intelligence reported Fox Bay (Spanish Bahía Fox) to be heavily defended by a crack 900 strong Argentine Infantry Regiment. A careful analysis of available maps and charts limited BRILLIANT’s attack options. Fox Bay was land locked with a narrow heavily defended sea entrance and surrounded by hills.

I was in no doubt to the importance of the mission and was central to the planning. Present at early briefings was the Officer in Charge (OIC) of a Special Boat Squadron (SBS) troop of 10 men that had recently embarked for an insertion ashore but not related to tonight’s tasking. I knew the OIC well, a wiry Royal Marine Office who I had previously served with on HMS ENDURANCE, the Antarctic Ice Patrol and Falkland Islands Guardship.

Intelligence didn’t report the exact position of the target ship but we assumed it to be near or alongside at Fox Bay East Settlement supplying the encamped 8th Infantry Regiment positions. Attack options excluded HMS BRILLIANT using its Exocet surface-to-surface sea skimming missiles as the narrow inlet would not provide good radar definition nor ideal attack geometry of a target alongside a jetty. A greater success probability would be the use of the two ship’s Lynx helicopters and its Sea Skua anti-ship sea skimming missiles but our assessment was that there was a risk of damage to civilian structures if the missiles went rogue. We were forced to consider another coup de grâce. The problem was getting inside Fox Bay without being detected from Argentine defensive positions.

Image: Captain John Coward HMS BRILLIANT (late Vice Admiral Sir John Coward KCB, DSO)

Image: Captain John Coward HMS BRILLIANT (late Vice Admiral Sir John Coward KCB, DSO)

I had visited Fox Bay a number of times during HMS ENDURANCE guard ship and hydrographic survey taskings between 1979 – 1981. I knew the topography of the settlements and surroundings. Captain Coward asked for a solution using the ship’s standard boat, the Halmatic Pacific Rigid Raider, to transit the Falkland Sound and enter the closed bay (undetected); to find, then to attack the target with available weapons. The Pacific had legendary sea keeping qualities and was compared at the time to be the Land Rover of the sea. So, we went away with some trepidation to plan a fast boat attack mission.

A fast boat approach through the defended narrows under cover of darkness would give an element of tactical surprise – until detected. If, and once through the narrows, the coxswain would drive the Pacific to close the Supply Transport Ship (so that we could positively identify it before attacking – a rule of engagement). Then we would attack it at speed to allow its small crew of 4 to attack with any hand-held weapons that we could bear onto the target. A tactic done years later with some effect by the Iranian ‘Boghammer’ speed patrol boats to merchant ships in the Straits of Hormuz. But what weapons could we use to disable a large ship?

On passage south, HMS BRILLIANT had embarked a light Milan anti-tank infantry weapon for use of troops during the land battles yet to happen. The Milan is a shoulder fired wire-guided missile; meaning the sight of the launch unit has to be aimed at the target to guide the missile. It had never been fired from a ship’s small boat. (On passage south, we had explored using the Milan from the rear cabin of the Lynx helicopter but drew a line after some measurements and lively brainstorming and said No Way). We would probably have had to stop or slow the ship’s boat abeam the target to allow for steady aim and fire. The SBS were to cover that aspect of the fire mission. My role, having the local knowledge, was to assist pilot the Pacific across Falkland Sound avoiding the masses of kelp forests (seaweed); a known snagging hazard to small boat propellers, and once inside the narrows to add to the small arms fire power, using a 7.62mm General Purpose Machine Gun.

Image: Halmatic Pacific Rigid Raider (similar to type used in 1982)

Image: Halmatic Pacific Rigid Raider (similar to type used in 1982)

Safe sea transit to Fox Bay would be extremely difficult because of the high risk of fouling the outboard motor propeller in the kelp offshore. At some stage we may have had to cut the engine and paddle through the kelp hugging the cliff line. With the winds and current (and cold) it would have been an impossible task even for the super fit SBS. (We had learnt from the retaking of South Georgia that small boat operations were fraught with risk and never to assume the environment would be on our side). The professionals (SBS) were concerned, having concluded their own risk assessment. The balance of risk was against getting away with an effective, stealthy method of attack. Somebody muted we would be dead in the water ‘quite literally’. We thought the plan to be suicidal and the SBS went to tell the Captain – not me! With the SBS out of the mission, I knew a helicopter attack option would be the one option remaining.

Helicopter Attack

The British Task Force used Greenwich Mean Time (UK time) throughout the war, so called Z Time. Argentina and the Falkland Islands were in Z-3 hours. Sunset at 20:15Z (UK time) which was 17:15 local time. The time difference was significant as we wanted to catch the Argentine defenders in the middle of their night (not the UK night) when we hoped the majority would be sleeping.

HMS BRILLIANT was dispatched to the south of Falkland Sound with instructions to be back with the Main Battle Group by daylight. It took 6 hours sailing in a heavy South Atlantic sea to reach the lee of East Falkland by 01:00 local time. We hoped Argentine forces ashore would be sheltering and sleeping from the bitter wind chill, or at least most of them. The passage was used to prepare the two ship’s Lynx helicopters. The Lynx aircrew pairing were:

XZ 729 C/S ‘Basher’ – Lt Cdr John Clark RN, Lt Paul McKay RN, Lt Chris Sherman RN, Royal Marine Mark Neat

XZ 721 C/S ‘Jimmy’ – Lt Cdr Barry Bryant RN, Lt Nick Butler RN, Royal Marine Pottsy Potts

As I was the only person with knowledge of Fox Bay, the responsibility of leading the attack was mine. A task I readily accepted. We huddled together in the ship’s flight office formulating a ‘Taranto’ style multi-direction airborne attack to take back to the Captain for approval. We looked at the recent signal intelligence which didn’t make comfortable reading.

Image: Some of the 900 Infantry defending Fox Bay 1982

Image: Some of the 900 Infantry defending Fox Bay 1982

Fox Bay is the second largest settlement on West Falkland. It is located on a bay of the same name, and is on the south east coast of the island. It is divided into Fox Bay East and Fox Bay West making it two settlements with an airstrip. Fox Bay was occupied by Argentine troops, around 900 men from the 8th Motorised Infantry Regiment and elements of the 9th Engineer Company. Worrying for us was the report of Roland and Tigercat Surface-to-Air Missile systems and 35mm twin and 20mm single barrel Anti-Aircraft guns defending the Argentine held ground. A helicopter is an easy target for air defence teams to shoot down!

The Target

The 5000-ton Argentine Navy resupply vessel ARA BAHIA BUEN SUCESO landed scrap metal workers on South Georgia in March 1982 which played an important part in the escalation of tensions between Britain and Argentina. Later, she was involved in blockade running to the Falkland Islands. She sailed from Port Stanley towards the Falkland Sound on 29 April and was resupplying the Argentine garrisons on the Islands. As a transport ship, she had no mounted guns but we assumed the crew, as augmented by Argentine military, would have small to medium calibre machine guns on the upper decks and possible shoulder launched weapons to repel an attack.

Image: ARA Bueno Suceso at Fox Bay jetty 1982

Image: ARA Bueno Suceso at Fox Bay jetty 1982

West Falkland has a mountain range running its length and a rocky cliff line similar to Devon and Cornwall. There are creeks and inlets that cut through the hills, perfect to fly low level and avoid detection. There are no trees and the terrain is largely grazing land so little chance of flying into something at almost zero feet (other than sheep), assuming we could see the ground. The sea approach into the Bay was bounded either side by hills rising to a 1000ft and measures ½ mile across at the entrance. Flying through the narrow gap would have provided an easy target for the defenders and downwind the Lynx carries a distinctive noise1.

1 Residents of Somerset often complained to the Westlands helicopter site at Yeovil of noise disturbance causing the Company to apologise to local residents and that it only performed Lynx night flying trials when it is was absolutely necessary.

Inside the narrows, Fox Bay opens slightly. Looking from seaward, the jetty of Fox Bay West was to the left and the jetty of Fox Bay East to the right with settlement houses close by. Fox Bay was not a fishing or trading port, so we knew any ship’s electronic signature that we picked up would most likely be Argentine.

A transport ship is a viable target for a Sea Skua anti-ship missile. Sea Skua is a semi-active sea skimming missile with a range of 1.6 to 8.2 miles. The launching Lynx would illuminate the target with its Sea Spray radar and the missile homing head would then home in on the reflected energy. Critical was the requirement for a good radar ‘lock’ signal to be maintained.

Image: Lynx helicopter sea skimming Sea Skua missile

Image: Lynx helicopter sea skimming Sea Skua missile

Sea Skua was still a relatively new British missile, just like the Argentine Super Etendard aircraft launched Exocet missile which had success on the attack on HMS SHEFFIELD, HMS GLAMORGAN, ATLANTIC CONVEYOR. We had technical notes concerning Sea Skua missile capabilities and limitations. We concluded that if the target ship was at the jetty then the likelihood of sustaining a good radar lock for missile time of flight was risky. If a Sea Skua missile receives intermittent radar lock signal during flight there is a probability of the missile ditching or flying through the settlement and causing civilian casualties.

We still did not know the exact position of the target nor the position of ARA BAHIA PARAISO which was used as a hospital ship. The 2nd Geneva Convention prohibits military attacks on hospital ships. Therefore, there was a need to positively identify any target by its name before attacking it. We decided that Lynx c/s ‘Basher’ would fly into Fox Bay from an overland hidden route and hunt the target down and Lynx c/s ‘Jimmy’ to loiter on the seaward side of the narrows as a distraction and armed with Sea Skua in case the ship made a viable target. Basher needed an alternative weapon to the Sea Skua missile in the confined attack space of Fox Bay so we called on the assistance of Lt Chris Sherman the ship’s diving and demolition officer.

A few weeks before, Chris had prepared a ‘homemade bomb’ around 60lbs plastic explosive and scare charges for operations to dismantle the captured submarine ARA SANTA FE during the South Georgia campaign. His bomb ingredients were packed into a Courage CSB beer barrel with a short time-fuse detonation. Our attack method was to hover taxi over the funnel of the ship in the dark and drop a similar fabricated bomb down the funnel with expectation that it would cause an explosion and a major fire. If, as we thought, the ship was carrying ammunition and fuel then resultant explosions would disable the ship. The delivery method was so ludicrous to be hilariously dangerous.

Image: Lt Chris Sherman (left) Ship’s Diving Officer & maker of the special delivery parcel bomb

Image: Lt Chris Sherman (left) Ship’s Diving Officer & maker of the special delivery parcel bomb

The plan was approved. HMS BRILLIANT was making fast passage to the Islands in a heavy sea. My stomach was churning perhaps more of anxiety than motion sickness. I was tired having not slept well in some days. I was running on adrenaline. I decided to take a shower. Running through my mind was my mother’s words to me as a child to always wear clean underwear in case of an accident. I dutifully put on a clean set of underwear under my flying suit and placed around my neck; the St Christopher medallion a gift from my parents at my first Holy Communion, my ‘dog tags’ giving name, blood group and religion and two phials of self-regulated auto-injector morphine for use in the event of treating casualties. I tried to catch a power nap but it was impossible with so many thoughts running through my head. I was scared. Those male hormones were running havoc, just like on a first date but worse! I was dutifully spurred by imagining what the men of Taranto would have been thinking prior to their mission.

I got dressed early into my flying immersion suit. I checked the contents of the suit pockets over and over again. In my right leg pocket, a tin containing a selection of escape and evasion survival aids; a pocket compass, a pen knife, a night torch, some boiled sweets, etc. In my left leg pocket, two extra Sterling submachine gun magazines, loaded and taped back to back for speed of changing magazines. In my left knee pocket, I had a folded map of West Falkland for use in the event of escape and evasion. In my right leg pocket, a spare 9mm Browning pistol magazine, the last chance saloon if entrapped during evasion by Argentine troops. I checked my armoured body vest that I would wear under the aircrew life jacket, particularly the lead plating which was fastened in pockets, one over my heart and one in the back pocket over my spine. I checked all again and then again. I loaded a fresh 9mm magazine even buffing the bullets as if they would fly faster and slotted it into the pistol that I had strapped to my left leg because confines of the tight cockpit meant I could not wear it on my preferred right side.

Image: The Sterling Submachine gun 1944-1994

Image: The Sterling Submachine gun 1944-1994

I am right handed so I practiced hand to left thigh, pistol out of holster, aim, shoot, time and time over until I got it down to seconds (with my eyes closed). Nerves were getting to me.

I walked aft to the helicopter hangar to speak to the air mechanics preparing the two helicopters for the mission, still a few hours away. I met up with Chris who was finishing preparations to his home-made bomb. It took two people to lift the bomb into the rear passenger cabin of the helicopter such was the weight of explosives inside. I briefed Chris where he would sit for the transit, and the dispatcher harness he would strap into to give him mobility to open the cabin door when running in for the attack, and practice in how to hand toss the bomb out of the cabin door. We secured the bomb behind my flying seat – some comfort! I checked the cabin mounted General-Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG) and that we had sufficient boxes of 7.62mm ammunition secured tightly with bungee clips to the cabin floor. Both Lynx would carry a Royal Marine to fire the GPMG. It was a surreal moment looking at the bomb thinking of the carnage if it had inadvertently exploded on HMS BRILLIANT. The bomb would have blown away the back end and all of the flight deck crew with it.

I went back to my bunk and checked over the contents of my flight suit pockets again, practiced weapon drills, said prayers and walked back to the hangar repeating my steps many times over. I was getting more anxious so I went to the bridge to view the night sky, it was still black and overcast. Looking at the chart with the Navigator we were south of East Falkland and in the lee of land giving protection from the north-westerly blow. I went over in my mind the attack plan which I would brief for a final time an hour before our scheduled take-off.

The Attack

John Clark would fly from the cockpit right seat and me in the left seat, with Chris Sherman and Mark Neat as cabin gunner in the rear cabin. We would launch in the 2nd Lynx with the ‘bomb’ and as much small arms ammunition that we could carry – we anticipated a fierce firefight to come. Nick Butler, Barry Bryant, and Potsy Potts as the cabin gunner would launch in the 1st Lynx armed with two Sea Skua anti-surface missiles, to fly to a sea rendezvous position and wait for us to join. It took 35 minutes from launching the 1st Lynx to moving the 2nd Lynx from the hangar, spreading the rotor blades and launching.

I had briefed the attack plan to the Captain and the ship’s warfare team an hour before launch. The forecast weather was for a strong wind at altitude, scattered cloud and a low freezing level. There was chance of seeing a half-moon in the sky rising to the east-south-east. The light from the moon and stars would not be to our disadvantage for night low flying. Both Lynx were fuelled to give a 2.45 hour endurance. HMS BRILLIANT was over the radar horizon to avoid any possible detection by Argentine forces making for a 70 mile sea transit to the target area.

HMS BRILLIANT after launch would close West Falkland as both Lynx would be running short of fuel on recovery.

‘Jimmy’ launched at 05:05Z time (02:05 local) in total silence from a sheltered position 5 miles south of Barren Island at latitude 5228S Longitude 05945W. Watching from the hangar, I could barely make out the black silhouette of ‘Jimmy’ as it launched into the night sky. The ‘high amplitude’ noise of the rotor blades seemed to take ages to dissipate but not enough to wake up the residents of Somerset! It then went eerily quiet as the flight deck crew set about moving ‘Basher’ to the flight deck.

Everyone knew their duty and few words were said. I once again checked myself over from head to foot to ensure I had everything. I weighed heavily and was sweating profusely as I waddled to the helicopter. I thought; ‘God forbid if I end up in the sea, as I would sink like a brick’. Finally, we were strapped in and working through the pre-start and take off checks. I entered the ships launch position, its intended track, Fox Bay and the rendezvous position with Jimmy into the doppler navigation system.

Image: Bursts of tracer fire illuminated the sky to our right towards the direction of the target

Image: Bursts of tracer fire illuminated the sky to our right towards the direction of the target

Navigation once airborne would be by dead reckoning on compass and stop watch (as it was for the aircrews’ of the Fairey Swordfish aircraft at Taranto). Without being able to update our navigation system by fixing method then its accuracy was not sufficient for this precisely planned time on target attack mission. We were operating in total silence so there was no radio chatter or use of the helicopters’ radar (until the target was positively identified). At 05:45Z (02:45 local) the lashings holding ‘Basher’ to the deck were removed and we got airborne flying into the night sky.

The helicopter rendezvous was 30 miles west of the launch position. ‘Jimmy’ flying a race track pattern at 60 Knots and 150 ft for ‘Basher’ to join at 300 ft both helicopters showing no lights; peacetime night flying rules would not allow this height separation but we were at war so the regulations went out of the window. It was a nervous join up and great credit to Nick flying ‘Jimmy’ to call ‘aboard’ as we headed on a northerly track to intercept land on West Falkland. We were now two blacked-out blobs flying low, a few rotor spans apart, at 140mph over the waves. The thought of a bird strike would have probably brought us both crashing into the sea but that was the least of our worries as we all concentrated hard on our tasks.

The small islands off Port Albemarle came into visual view on dead reckoning time at about 1.5 miles. We took a pre-briefed 45 degree course change to follow the coast north towards Port Edgar keeping the cliffs in my left visual sight. At 06:15 UK time (03:15 local) I visually identified our land ingress point on Edgar Ridge. The offshore rocks were flashing by. The Lynx formation split; ‘Jimmy’ breaking right to fly a pattern over the sea south of Fox Bay and ‘Bashar’ heading left to follow an inlet stream running west of the settlements to position ourselves in the high grounds to the north-west of Fox Bay for an attack run in.

John was concentrating hard not to fly into the ground. My eyes were out of the cockpit navigating the terrain giving small course alterations. We were in a dry creek. I recall seeing boulders above shoulder height and thinking that John was flying incredibly low but the element of surprise was vital. We had to stay below the ridge lines to avoid visual and anti-aircraft radar missile detection. Also, to mask the noise of the helicopter’s rotor blades that can be heard for miles away in the still of the night. To our dismay, and still 8 miles from the target we saw isolated bursts of tracer bullets in the sky to our right and towards the direction of Fox Bay. ‘Shit’ we cried, ‘that’s the element of surprise gone’ but we had to block that thought out of our minds. ‘It cannot be us they are firing at’ we thought, perhaps it was ‘Jimmy’ that had alerted the defenders. The Argentines would be awake by the time we arrived on target! But what were they shooting at?

I must have been momentarily distracted and took my eye off the boulder stricken creek running below because the land ahead was suddenly rising sharply. John went hard left and pulled max power as we flew up and over a high point (a 617 Squadron Dam Busters moment). Thank God there was no low cloud hiding the mountain peak that night. We shot over and down into a saddle between ridges and over a lake of still water which I identified on the map. I briefly caught sight of Fox Bay to the right, the water of the bay looked still and shinning bright under the sky. Where was the cloud cover when one needed it? I gave John a new course to fly to take us further away from the bay, and for a while we thought we had got away with being detected. We set up for a run-in to the target from the mountain areas to the north of the bay. As we flew over the last ridge heading south we could see the bay ahead but not the target. John went extremely low and fast, following a flat col between high ground down the into the bay.

Image: John was concentrating hard not to fly into the ground as we flew over the mountain range and into Fox Bay ahead.

Image: John was concentrating hard not to fly into the ground as we flew over the mountain range and into Fox Bay ahead.

I had calculated it would take 90 seconds to reach the settlement. I could see the outline of what looked like a vessel alongside the jetty. John saw the silhouette and flew low across the bay directly for it. I opened the left cockpit window. I could see strips of land, and then water below, and an occasional hut or similar shape to my left. John had the water of the full bay to his right. Confident we had a target in sight and the absence of any other vessel visual, we pressed home with a ship identification and ordered the guys in the back to open the cabin doors and make ready to engage the target with the bomb and GPMG.

With less than 60 seconds to time on target we drew red and yellow tracer fire ahead and moving towards us from the directions of Fox Bay East Settlement. We were over the water to John’s right, and over land to my left and there was little cover to hide. Committed, we flew a straight line to the jetty. I aimed my submachine gun out of my window. The silhouette of a ship was getting larger, it looked to be ARA BUENO SUCESO! Chris was ordered to ‘prime the bomb’ which had about a minimum safety 10 second fuze.

I briefly saw land below me and what I thought to be a hut or building and some telephone like wires. John still had the water to his right so we must have been flying along the beach line. John came up the stern of the ship and slowed to an almost hover taxi speed with the searchlight on to read the name. We had to be sure it was not the hospital ship. No marking was visible so John taxied up along the starboard side towards the bow. I shouted with certainty over radio and intercom ‘BUEN SUCESO BUEN SUCESO’. It was a case now of positioning the helicopter over the funnel to drop the bomb – seconds remained

What I saw to be heavy anti-aircraft calibre tracer shells and more accurate small arms tracer fire opened up to our immediate left, and then from ahead and below. John flung the Lynx into a series of what probably would have broken the Guinness book of records for anti-evasion G-manoeuvre. I fired my sub-machine gun, set to automatic fire, onto the ship and dark shapes moving immediately below and to my left emptying both magazine rounds including a fast magazine change (all that practice had paid off). The heavier calibre fire momentarily stopped but Argentine red and yellow tracer arcs of fire were arriving from all directions and flying directly at us.

John broke right, stuffing the nose down, and pulling in power to accelerate away at very low level and back over the bay. It was no more than a second or so of total confusion. The Argentine tracer fire became more intense. We were flying literally on top of the water. The bullets seemed to be passing very close, down either side and over the top of the fuselage and rotor blades. If hit, and at the speed and height we were flying a ditching would not have been survivable. It seemed inevitable we would die there and then. If that was the case, then I would have been disappointed to die with no last thought, ‘little about this valedictory mission would be remembered’ but we knew we had given it our very best.

Image: 2nd of the night’s attack Sea Harriers strafe the target

Image: 2nd of the night’s attack Sea Harriers strafe the target

Then an even worst nightmare dawned on John and I in the cockpit. We briefly glanced at each other, and thought ‘Where is the f*@!ing bomb?’ The order for Chris to prime the bomb had been given but I did not see it leave the cabin from my side onto the ship. We screamed over the helicopter intercom but during the evasive manoeuvre his intercom connection and that of the marine gunner must have been disconnected. The bomb exploding in the helicopter would have made a spectacular sight to the defenders that night. I turned to look behind and saw both men grimly hanging on. It was a while later when intercom to the rear cabin was restored that Chris said he had tossed out the bomb during the evasive manoeuvre. Mark apparently had lost his balance during the g-force manoeuvre and flew out of the cabin door, holding onto the cabin mounted GPMG to stop himself from falling out of the Lynx.

We took sporadic fire as we flew over Fox Bay West Settlement and into the hills. Once clear we took stock of any damage and a decision to force land and to escape and evade, or try to return to the ship. We called ‘Jimmy’ over the radio but no reply, thinking he may have been shot down. ‘Basher’ was responding to flying control movements so we returned gingerly but expediously to the ship, pleased to be alive. Only after landing did we learn that ‘Jimmy’ had landed before us. ‘Jimmy’ didn’t see action that night other than the fireworks display inside the bay. Watching the firefight from a distance they didn’t think we had made it.

Questions were asked in the aftermath of the failed mission. Only after recovery did we learn that two Sea Harriers from HMS HERMES had later attacked the ship using its 30mm ADEN cannons rather than general purpose bombs because the ship was so close to civilian homes.

After the attack, ARA BUENO SUCESO did not sail again and remained moored in the bay until after the war where she was towed out to deep water and sunk by a combination of naval gunfire and fire from Sea Harriers.

Postscript

Images: Cesar Moreno 1982 Paul McKay 1982 Cesar Moreno 2019

Images: Cesar Moreno 1982 Paul McKay 1982 Cesar Moreno 2019

It’s a story that took 38 years to tell. In the main part because nobody cared, it was a mission failure. During immediate post action debriefing, someone asked (not direct to my face) if there had been a lack of courage displayed in facing the danger, a stigma that still haunts me today. Honours for the war were divided amongst the ships’ aircrew post war. I received a commendation for Fox Bay which went someway to appeasing my feelings. In it, there was reference to my cool return of fire using a hand held gun out the door of my aircraft killing and wounding a number of the enemy manning an anti-aircraft position.

I wanted to know more. I tried through UK official archives to seek more answers but to no avail, so I went to Argentine sources to help me track down the guys who I shot at. The result was coming into contact, through Argentine veteran associations, with Cesar Moreno, one defender that I badly injured that night. Great friends today, we hope to meet face to face sometime in 2021. I had made some inner peace at last.

But back to ‘England expects….’. Since WW2, it could have been Korea, Aden,

Northern Island, Falklands, Balkans, Gulf, Iraq or Afghanistan or any other theatre where those who serve do what they are expected to do when challenged and go that extra mile. It’s what makes the British service man or woman unique.

Innovation, skill, daring and bravery is something we do when the chips are down. There are many who were killed on such missions that we will always honour. There are also many veterans that have painful memories and suffering from the demons of their own ‘hairy’ stories.

For me, I have finally found some piece by telling in part my story which I hope helps others in a similar predicament.